To print this article, all you need is to be registered or login on Mondaq.com.

Chanel recently emerged victorious in its trademark infringement

and false advertising lawsuit against luxury reseller What Goes

Around Comes Around (WGACA). A jury in the U.S. District Court for

the Southern District of New York awarded Chanel a unanimous

verdict on all counts of liability, plus $4 Million in statutory

damages for willful trademark infringement in connection with the

sale of counterfeit bags that were never authorized for sale by

Chanel. The case will now proceed for Judge Louis Stanton to decide

what equitable relief Chanel may be entitled to, including a

potential injunction and disgorgement of WGACA’s profits.

In the world of luxury fashion, where the allure of exclusivity

meets the burgeoning appeal of “vintage” products, this

legal battle casts a spotlight on the dynamics between intellectual

property rights and the thriving market for pre-owned goods.

Whether the media attention surrounding this decision will cause

consumers to think twice about purchasing products from luxury

resellers such as WGACA, The Real Real1 , and others,

remains to be seen. Regardless, it should cause resellers

to re-examine their marketing and sourcing decisions, and

provide luxury brands with confidence that they have some recourse

to protect their intellectual property in the resale market.

This article provides a brief summary of the lawsuit and tips

for brand owners to protect their rights in the resale market.

THE ESSENCE OF THE DISPUTE AND THE JURY VERDICT

Chanel is a brand synonymous with haute couture and an

unyielding dedication to protecting its intellectual property. In

March 2018, it sued the luxury retail company WGACA in connection

with its unauthorized resale of CHANEL branded products. Its

complaint was based in large part upon the allegation that

WGACA’s conduct implied a non-existent endorsement or

affiliation with Chanel that was likely to mislead consumers and

dilute the brand’s esteemed reputation. These allegations were

bolstered by the fact that some of the products sold by WGACA as

“authentic” CHANEL branded products were proven to be

counterfeit.

WGACA countered Chanel’s claims by championing the

authenticity of its offerings and asserting that the law’s

first sale doctrine entitled it to resell genuine Chanel items.

The parties participated in a nearly month-long jury trial in

January 2024, after which the jury rendered a unanimous verdict

finding WGACA liable on all counts, and decisively finding that

Chanel had proven:

- Its claim for trademark infringement, false association, and

unfair competition based on WGACA’s use of Chanel’s

trademarks or other indicia of Chanel; - That WGACA acted “willfully, or with reckless disregard,

or with willful blindness in its use of Chanel’s trademarks or

other indicia of Chanel” and its use of hashtags that included

the Chanel mark; - That WGACA infringed Chanel’s trademarks and engaged in

unfair competition by creating and using various hashtags

containing “Chanel” or “Coco Chanel” to

advertise and market WGACA products on social media; - That certain Chanel branded products sold or offered for sale

by WGACA were not authorized for sale, differed materially from the

product authorized for sale, or did not pass through Chanel’s

quality control procedures; - That certain Chanel branded handbags sold or offered for sale

by WGACA were counterfeit; and - That WGACA engaged in false advertising and acted willfully,

with reckless disregard, or with willful blindness in its false

advertising.

IS RESALE ALLOWED UNDER THE LAW?

The result in the Chanel case does not change the law,

and the application of the law will depend upon the facts of each

case. However, this verdict provides guidance to both resale

companies and brand owners with respect to the delicate balance

between permitted resale of genuine products, and protection of a

brand’s valuable intellectual property rights.

The legal doctrine of “first sale” provides that once

a genuine product has been sold, the purchaser may resell the

product without recourse from the intellectual property

owner.2 However, there are some exceptions. Resale is

not lawful if the goods are not “genuine”, or are

“materially different” from the goods that were

originally authorized for sale by the brand owner.3

Examples of goods that are “materially different”

under the law include products that have been materially altered

via new materials or designs that were not subject to a brand’s

quality control measures (such as the unauthorized alteration of

the bezel of a Rolex branded watch), or that include packaging,

labeling, ingredients, or materials that are not authorized for

sale in the U.S. market.4 Products that are not

“genuine” under the law include products that have not

been cleared for sale by the brand owner because they did not meet

the brand’s quality control measures, such as defective

products or products created or distributed by factories without

the brand owner’s permission.5

The right to resell a genuine product also does not give the

re-seller the right to use the brand owner’s trademarks and

other intellectual property in a way that is likely to lead

consumers to believe that the brand owner has endorsed, or is

somehow associated with the reseller. In particular, while the

doctrine of “nominative fair use” permits a party to use

a trademark or brand name as necessary to describe another

party’s product, it may only use a mark so much as necessary to

identify the product.6 A reseller is not allowed to use

a trademark or other brand indicia in a way that would likely

mislead consumers into believing the brand is endorsing,

sponsoring, or is somehow affiliated with the reseller or its

resale business.7

Therefore, a reseller may state that it is reselling a Chanel

bag, if in fact the bag is a genuine, unaltered, Chanel bag.

However, making excessive use of trademarks or other indicia

associated with the brand to promote a resale business is more than

the law allows because it is likely to cause consumers to falsely

believe that the brand is endorsing the resale.

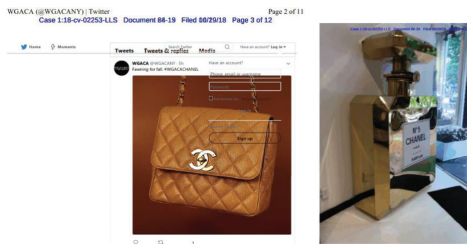

In the Chanel case, WGACG prominently and persistently

used Chanel’s marks and other indicia associated with the

famous fashion house to promote its resale business, including the

hashtag “#WGACACHANEL”, references to the brand’s

founder, images from Chanel advertising campaigns, and the

prominent display and sale of promotional products such as

notepads and tissue boxes that were gifted at fashion shows but

were never authorized for sale by Chanel. Some examples of this

conduct from the Chanel court filings are included below.

WGACA’s claims that the Chanel branded products it sold were

“guaranteed authentic” (such as the claim shown below),

and letters purporting to authenticate such products, also likely

lead to the jury’s decision that WGACA’s conduct would

falsely lead consumers to believe that Chanel endorsed the products

sold by WGACA and/or its resale business.

POLICING RESELLER ACTIVITY AFTER THE CHANEL

VERDICT

The Chanel decision confirms that while brands cannot

stop the resale of genuine products, they may exert some control

over the manner in which their intellectual property is used

– and how their products are advertised and sold – in

the secondary market. The jury verdict in the Chanel case

may cause luxury resellers to re-examine their advertising

practices and authentication claims. It may also cause the

resellers to be more receptive to requests from luxury brands to

refrain from conduct that is likely to confuse consumers and

violate the brand’s intellectual property rights.

If a brand is unsuccessful in convincing an unauthorized

reseller to correct false or misleading practices, litigation may

be a necessary step.

If a brand is unsuccessful in convincing an unauthorized

reseller to correct false or misleading practices, litigation may

be a necessary step. While the outcome of any legal dispute

would depend upon the particular facts at issue, recent cases

including Chanel v. WGACA, 8

demonstrate the courts’ willingness to protect brands’

intellectual property rights and to hold resellers accountable for

unauthorized activities and false advertising.

If a reseller has a large inventory of one or more style

of a brand’s product, it may be an indication that the product

is counterfeit and/or that one of the brand’s distributors is

in violation of its agreement with the brand.

STEPS FOR BRANDS TO CONSIDER TAKING

Brands should consider the following actions to monitor and

protect their intellectual property in the resale market.

Footnotes

1. Chanel also sued luxury reseller The Real Real in 2018

in a case captioned, No. 1:18-cv-10626, Chanel, Inc. v. The

RealReal, Inc. (S.D.N.Y.). According to the court docket, this case

is currently suspended pending mediation.

2. E.g., Coty Inc. v. Cosmopolitan Cosms. Inc., 432 F.

Supp. 3d 345, 349 (S.D.N.Y. 2020) (citing Polymer Tech. Corp.

v. Mimran, 975 F.2d 58, 61 (2d Cir. 1992) (quoting NEC Electronics

v. CAL Circuit Abco, 810 F.2d 1506, 1509 (9th Cir. 1987))); Liz

Claiborne, Inc. v. Mademoiselle Knitwear, Inc., 979 F. Supp. 224,

230 (S.D.N.Y. 1997).

3. E.g., Zino v. Davidoff SA v. CVS Corp., 571 F.3d 238,

243 (2d Cir. 2009) (citing Polymer Tech. Corp. v. Mimran, 37 F.3d

74, 78 (2d Cir. 1994); Original Appalachian Artworks, Inc. v.

Granada Elecs., Inc., 816 F.2d 68, 73 (2d Cir. 1987)).

4. See, e.g., Rolex Watch USA, Inc. v. BeckerTime,

L.L.C., No. 22-10866, 2024 WL 301768, at *3 (5th Cir. Jan. 26,

2024); Societe Des Produits Nestle, S.A. v. Casa Helvetia, Inc.,

982 F.2d 633, 638 (1st Cir. 1992).

5. See e.g., El Greco Leather Prods. Co. v. Shoe World,

Inc., 806 F.2d 392, 395 (2d Cir. 1986).

6. Laatz v. Zazzle, Inc., No. 22-cv-04844-BLF, 2023 WL

4600432, at *14 (N.D. Cal. July 17, 2023).

7. Id. (citing Applied Underwriters, Inc. v.

Lichtenegger, 913 F.3d 884, 894 (9th Cir. 2019).

8. See also Rolex Watch USA, Inc. v. BeckerTime, L.L.C.,

No. 22-10866, 2024 WL 301768, at *3 (5th Cir. Jan. 26, 2024)

(Affirming the district court’s holding that BeckerTime sold

watches that were “materially different than those sold by

Rolex” and finding that modifying watches with “added

diamonds,” “aftermarket bezels,” and aftermarket

bracelets or straps constituted an infringement of Rolex’s

intellectual property rights).

9. Unauthorized use of copyrighted materials, including

images from ad campaigns and brand websites may give rise to claims

for copyright infringement.

Originally Published by The Intellectual Property &

technology Law Journal

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.

#Chanels #Trademark #Infringement #False #Advertising #Win #Brands #Protect #Rights #Resale #Market #Trademark